When Caring Hurts

“A compassionate doctor and nurse insist I promise them that I won’t take a desperate client home with me. Our client, an unwell older man, is going to be put on the street when the addiction clinic closes. We’re already an hour past closing. There is no detox bed that will take him; the ambulance workers assess that he doesn’t require emergency services; support workers are unable to assist because there is a warrant for his arrest; the police say they have a warrant for him but will not arrest him at this time; and there are no shelter beds. Armed with a load of clean secondhand clothes, which he doesn’t want to put on until he is able to have a shower, I walk alongside his sketchy shuffle up to an emergency shelter where he lines up outside and will wait for a few more hours to possibly get mattress space on the floor. I am going to return to the clinic: I am turning around. I know I will never be able to forget this moment of physically turning my back on him. Nothing in my professional training has prepared me for the waves of shame, betrayal and dishonour that go through me. I put one foot in front of the other and walk away from this suffering elderly man. I return to the companionship of the doctor and nurse as we keep each other from taking this man home. I still look for him.“

This was a story included in a 2011 article written by Viki Reynolds. Read here Resisting-burnout-with-justice-doing.pdf

In 2011, Vikki Reynolds published a now-seminal piece titled “Resisting Burnout with Justice-Doing.”

She described walking away from a suffering elderly client she couldn’t help—because the system had no detox beds, no shelter, no care. As she turned her back, she felt waves of shame, betrayal, and dishonour.

At the time, Reynolds framed this as spiritual pain and burnout.

But we know more now.

In the years since that article, the field of ethics and trauma has evolved. What she described was not just burnout. It was moral distress—and, possibly, moral injury.

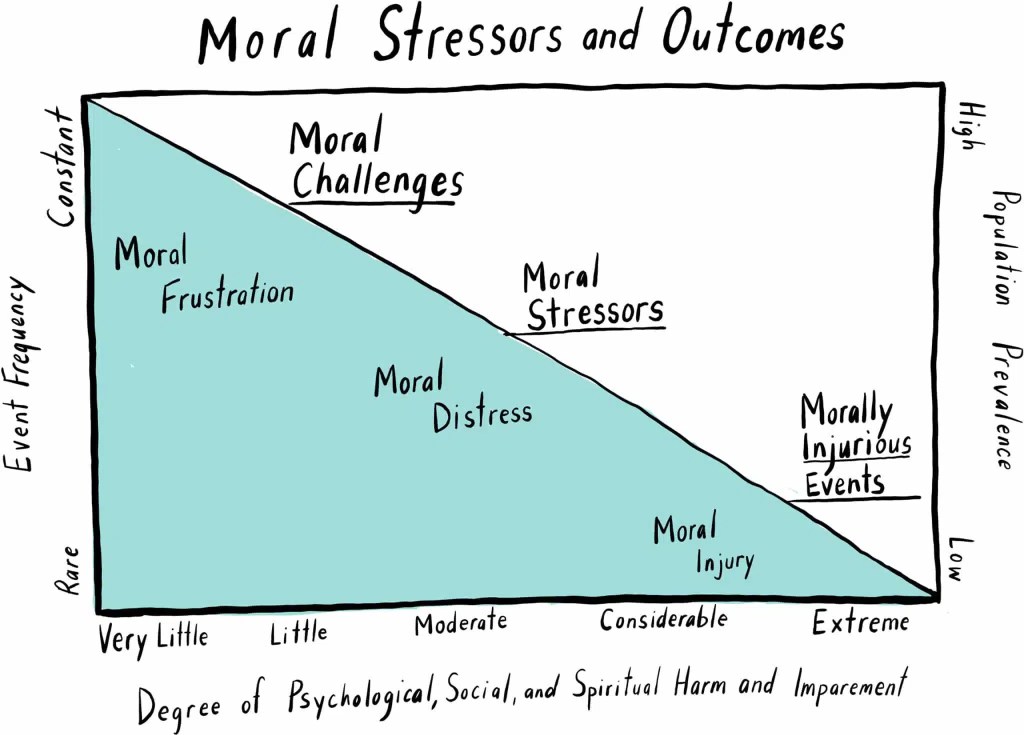

What’s the Difference? A Continuum of Moral Harm

Caring professionals experience ethical pain in many forms. Here’s how we now understand it:

1. Moral Challenge

An event or situation that activates your ethical awareness.

Example: A hospital policy prevents a nurse from spending time with a dying patient.

You feel tension—but you can act in line with your values.

2. Moral Distress

You know the right thing to do, but you can’t do it—because of institutional constraints, legal risk, power imbalances, or fear of repercussions.

Reynolds’ moment—walking away from a client who needed shelter—is a textbook example.

This is not just emotional distress. It’s ethical violation of your own core values.

3. Moral Residue

Unresolved moral distress builds up over time—layer upon layer. You keep turning away, biting your tongue, watching systems fail people you care about.

Eventually, it changes how you see yourself.

“Am I complicit?”

“What kind of worker am I if I keep surviving this?”

4. Moral Injury

A rupture in your identity, sense of self, or relationship to your work.

It can happen suddenly—from one catastrophic ethical betrayal—or gradually, after years of accumulated residue.

You no longer feel like the same person.

You feel contaminated by the work.

You can’t “recover” through self-care because what’s been broken is ethical, not just emotional.

Image retrieved from What is a moral injury? • Healthcare Salute

Why a Narrative Approach? Because This Is About Identity, Not Just Impact.

Many of us enter caring work because of our values—justice, dignity, care, truth-telling.

But those same values are exactly what get violated in morally injurious systems.

Vikki Reynolds reminds us:

“The problem of burnout is not in our heads or our hearts, but in the real world where there is a lack of justice.”

What we’ve been calling burnout is often something deeper: a grief for what we couldn’t do, a shame for what we were asked to allow, a slow erosion of our own ethical footing.

And that erosion doesn’t just hurt. It alters who we are.

Moral injury is not just about trauma—it is about identity.

That’s why a narrative approach matters.

Michael White, co-founder of narrative therapy, wrote:

“When people have been through significant and recurrent trauma … their ‘sense of myself’ can be so diminished it can become very hard to discover what it is that they give value to.”

Moral injury corrodes our internal compass.

It shrinks our sense of possibility.

It convinces us we are complicit, inadequate, or contaminated—when really, we are injured.

Narrative practice offers a way back.

It doesn’t ask us to recover.

It asks us to remember what still matters.

It helps us re-author who we are, in a world that tried to make us forget. And in that, we heal.

Narrative work does this by:

- Surfacing the values that were violated—but also lived through resistance

- Restoring identity not as diagnosis, but as story

- Locating injury in the world, not just in the body

- Connecting people in solidarity, not just support

- Inviting collective ethics to hold the pain, not just individual coping strategies

As Reynolds proposes, the antidote to moral injury is not just resilience.

It is solidarity.

It is collective meaning-making.

It is refusing to carry systemic harm alone.

We use narrative because it refuses to make the pain private.

Because stories are how we remember who we are—

and who we might still become.

In Episode One, we begin to share story.

Leave a comment